Käthe Kollwitz - Line and Purpose

Art and politics actually go together beautifully, when the meanings are profound and heartfelt

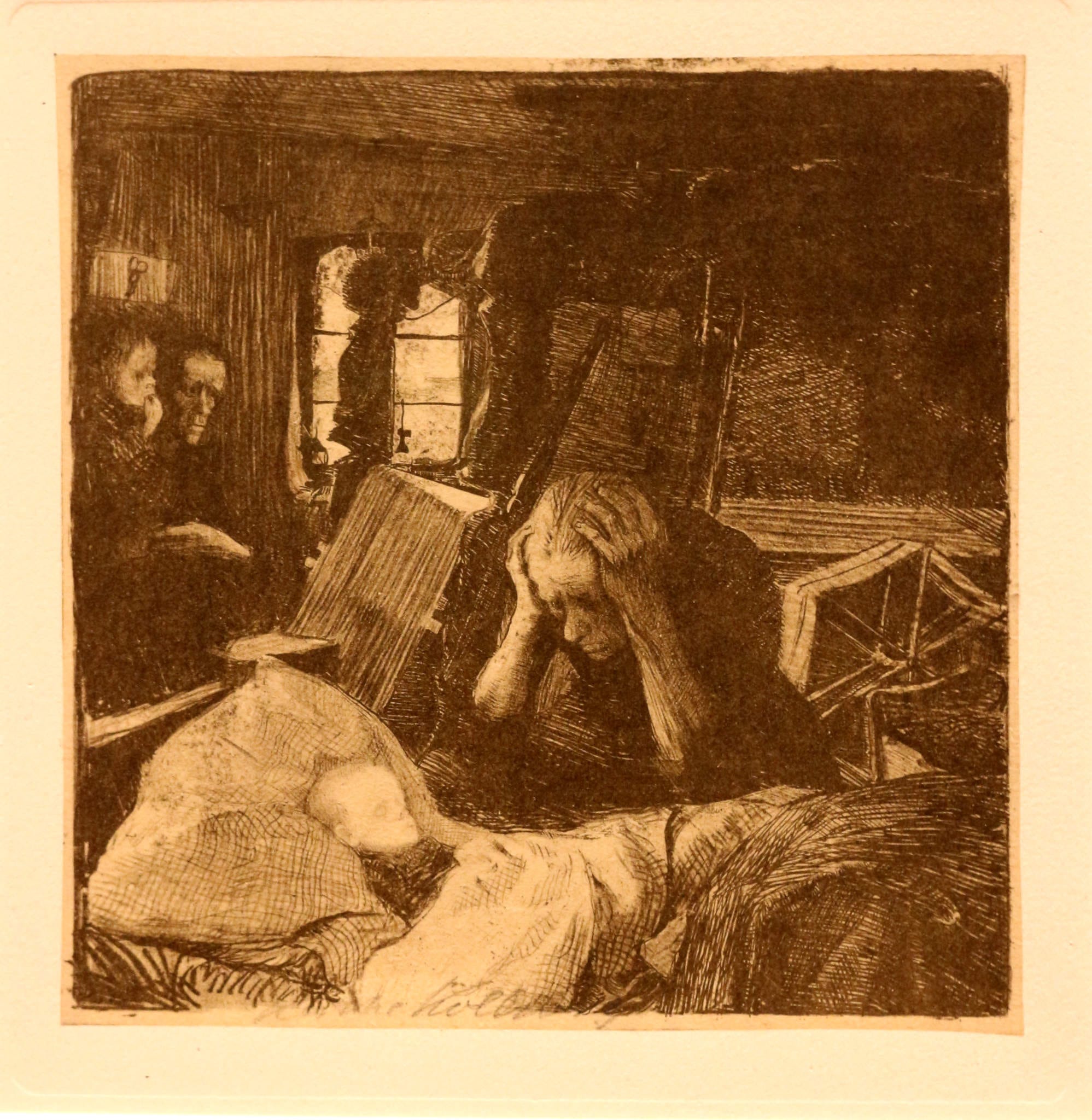

March of the Weavers (top image)

I am continually amazed by the valuable clues we uncover when we dig into art history. These clues are never confined to the artist themselves or their work, but enrich our understanding of the places and years with which they interacted, the development of understanding within a struggling human over time, and the ways in which our witness and communication can and cannot foster change in the world.

There are, it must be said, some artists whose work is so irrelevant and poorly achieved that their stories speak far more about celebrity and the emperor's new clothes than they do to anything substantial or culturally important. But for those who were struggling with great vision, great empathy, or great yearning for change, we often find an extra-vivid engagement with their historical period.

Käthe Kollwitz is an excellent example of someone who never stopped striving, and kept courageously working to metabolize even the most difficult of lessons, throughout her long life.

She was born in 1867 in Koenigsberg - which had for centuries been the royal seat of Prussia (before its transfer to Berlin), and since the second world war has been Kaliningrad - an "oblast" or enclave belonging to Russia - originally for strategic reasons (the base of the Baltic Fleet) but more recently also an important economic centre for Russian business and a top rated city to live in.

Need - from Weaver's Revolt - 1893-1897

We don't often remember this, but even though the self-destruction of the Holy Roman empire during the thirty years war lead, in 1648 to some of the earliest formal nation-states (as opposed to outright kingdoms), like Saxony, Prussia, Bavaria and Austria, (most of) these German states weren't actually united into the nation of Germany (under Hindenburg) until 1871, very late in the game by European standards. The emphasis was on science and industrial development, right from this formation moment - progress at full speed, and even some of the great thinkers in their rival powers recognized the German nation had a right to consider itself under-resourced, compared to the other European states which had achieved unity of territory and focus much earlier.

I say all this only to point out that she grew up in a very young, dynamic and optimistic future-facing nation, rapidly pushing to modernize, urbanize, industrialize, and finally transform itself into the great power it soon became (the dominant industrial economy in Europe, in less than thirty years).

Her father was a stone mason and builder, and a leftist political radical, her mother was the daughter of Julius Friedrich Leopold Rupp (a name with irresistibly musical meter), who was a man of extraordinary principle, and after run-ins with the state and church hierarchy, finally founded the first free protestant congregation in Koenigsberg which was specifically based upon absolute freedom of conscience for every parishioner. Social progress was far more important to him than the sanctity of repressive institutions.

Death - from Weavers Revolt

Her grandfather's principle-driven socialism had a huge impact on her thinking, and also on the way her family responded to her early display of artistic talent. Her father got her art lessons at age 12 and by the time she was 16 she was an avid realist who loved drawing the working class people she saw passing through her father's business. But there was nowhere in town for her to continue her studies - no females were allowed in the Koenigsberg academy - so she had to travel to Berlin where she enrolled in an art school for women.

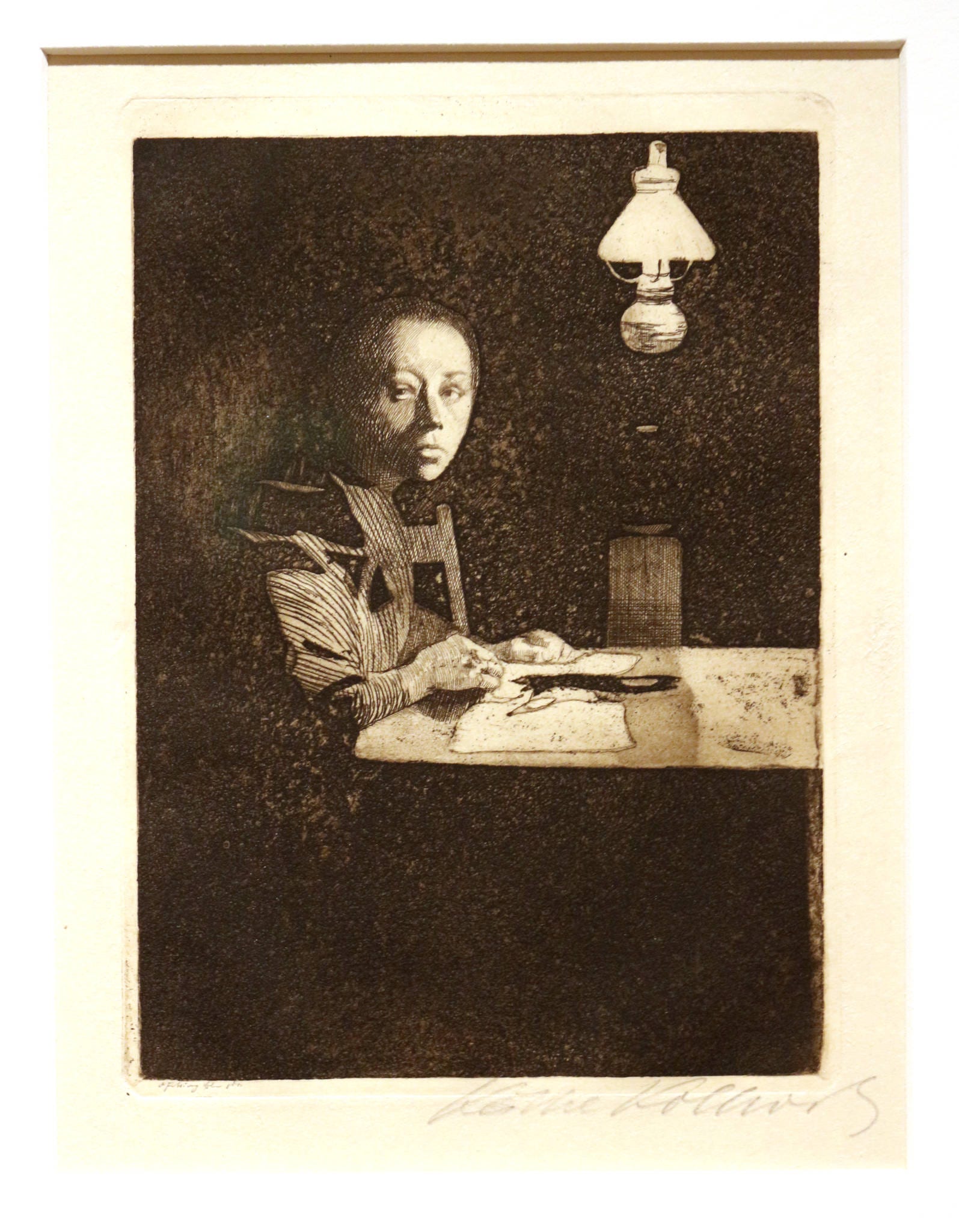

I think my all-time favourite description of art school in the old days comes from Emily Carr in her brilliant book "Growing Pains" - and from working as a model in art school myself, I have come to suspect one part of this arc remains identical - the best thing about art school is not the specific teacher one encounters (though of course a brilliant one is a fantastic boost, and can change your life) but rather the range of techniques and approaches you are exposed to, as a forming artist. She tried painting (and many years later also studied and mastered sculpture), but she found her greatest satisfaction and made her most profound impact in printmaking - lithography, etching and woodcuts.

I found another interesting clue in her story when I read she that she met her husband to be, Karl (then a medical student) when she was only 17, but though they were soon engaged, they weren't married until she was 24, a year after she had finished her studies first in Berlin, then later Munich, and had come home and established her own independent art studio in Koenigsberg.

Conspiracy - from Weavers Revolt

When she did finally marry Karl (1891), she moved to Berlin so he could open a medical clinic for the poor. One can't help thinking the sacrifice of her own studio was made easier by the principle involved. Interestingly, she encountered even better subjects for drawings of the working class in her husband's medical clinic (part of their large apartment) than she had in her father's offices.

She even once said that "Compassion and commiseration were at first of very little importance in attracting me to the representation of proletarian life; what mattered was simply that I found it beautiful." But as she got to know the struggling people who came to her husband for medical help, especially the women, who often asked her for help also, her grandfather's old philosophy was reignited on a new foundation - no longer inspiring words but her own direct witness - and this passionate perspective never left her afterward, even when she was in every other way bereft.

Tavern in Konigsberg (study for Germinal)

When we look at historical art, we far more often encounter kings and generals than peasants and workers (money has always edited the official record) - and men are usually the key figures, with women relegated to the role of helpless prize being fought over.

But Kollwitz was at the beginning of a transformation - one of the earliest to depict strong women and men of the working class in a realistic and yet still heroic light, and also one of the first principled and dedicated anti-war artists.

I was once a young idealistic socialist myself, so I can really relate to her searching for thematic inspirations for large works that could speak usefully. She was well into studies for a series of illustrations based upon a novel by the great French Novelist Emile Zola (Germinal) when she saw a play about the tragically unsuccessful "Weavers Revolt" in Silesia in 1844, and this play and the history behind it ultimately inspired her first great print series "The Weavers" several of which are included here.

Storming the Gate - from The Weavers

The series of three lithographs and three etchings with aquatint took her six years to produce, which might seem surprising until we realize she was not only helping her husband's medical practise, but also raising two small boys (born in 1892 and 1896). When The Weavers was publicly exhibited in 1898 it was a sensation and was nominated for an award - but the Kaiser (Wilhelm II) personally intervened, saying "A medal for a woman, that would really be going too far."

Self Portrait at a table - 1896

In the early years of the new century (her thirties) she worked on a new series, based upon an older peasant uprising - and she even found a heroine with whom she identified (a real boost, when you are trying to representing a long ago period, with great emotional honesty). As part of her research for this project she travelled to Paris and she studied sculpture while she was there - she even won a year with a free studio in Florence, as a prize for one of the pieces. This series, "The Peasant War" completed in 1908, is considered by some her finest - etching masterworks. The free year in Florence (1907) produced little art - but did charge her artistic batteries with enough renaissance inspiration to last her the rest of her life.

Uprising - 1899

Some artists repeat themselves, but the most interesting keep learning as they go and Kollwitz was in this group. As she got older she kept in touch with the newer movements, and rebuilt her own drawing style with many brand new modern design ideas from the Bauhaus and Expressionist movements in particular. (To this day she is claimed by both the realists and expressionists).

Her younger son Peter died in battle in the second month of the first world war. Consumed with grief, she struggled to put it into some artistic form for many years, but destroyed her first attempt at a monument in 1919, and started from scratch six years later. It was finally finished in 1932, which itself conveys the scale of her depression better than any quote or witness could.

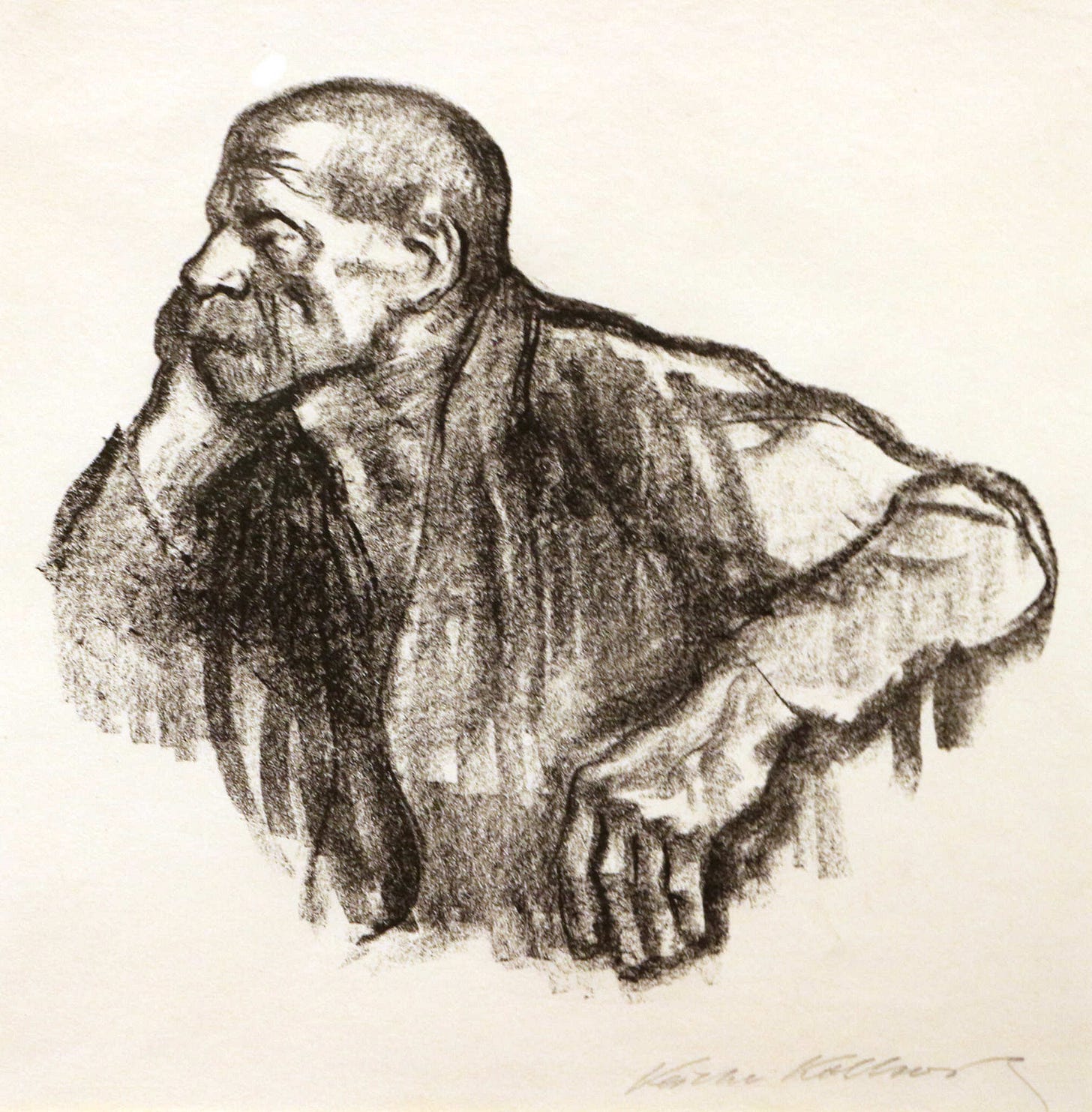

Pensive Woman

Just after his death she was quoted talking about women being "endowed with the strength to make sacrifices more painful than giving our own blood. Consequently, we are able to see our own fight and die when it is for the sake of freedom." But later in the war she no longer tried to justify his sacrifice, and instead worked hard and at no small risk to herself to prevent more needless death. When the state appealed for old men and young kids to volunteer in the last few months of the war, when things were getting desperate, she made a striking piece called, "Seed Corn Must Not Be Ground" - a powerful anti-war message to this day.

Municipal Shelter - 1926

Her fiftieth birthday retrospective was held in 1917 - with the war still raging - at the gallery of Paul Cassierer - a German art dealer important in bringing attention to Van Gogh and Cézanne, among many others. Despite her lingering depression post-war, she continued working vigorously - no lack of themes or powerful ideas to convey. Her cycle "War" was done in woodcut form, and often specifically lampooned or upended the official war propaganda, to create lastingly resonant appeals for peace. I think our understanding of people like George Grosz and Otto Dix changes when we realize they were relative kids (in their late twenties) post-war, when she (into her fifties) had already been exploring that passionate working class field for decades.

The Carmagnole - 1901

Her powerful technique and politics in combination also put the Belgian printmaker Frans Masereel (who was George Grosz's best friend in the mid twenties) into a new context. His wordless woodcut novels are an under recognized landmark in sequential art - but he was not aiming at innovation in form so much as function. He wanted to make inspiring working class novels which didn't need translation, and didn't rely upon high literacy to be fully appreciated. (You must keep your eye out for a copy of his masterwork "Passionate Journey" - exquisite and inspiring, both technically and philosophically).

Seated Worker - 1923

In 1920 Kollwitz became the first women elected into the Prussian Academy of Arts, which meant a decent salary, a spiffy studio, and a prominent teaching position. By 1928 she was the director for the Master Class for Graphic Arts at the Berlin Academy - but once again, the world outside was just about to mess with her well earned modicum of happiness and recognition. When the Nazis rose to power a few years later, all socialists and resistors of conscience were immediately removed from teaching positions, Kollwitz included - they even took her work out of the galleries where it hung, and she was forbidden to exhibit.

She did get teaching and citizenship offers from all over the world (especially on her 70th birthday in '37), but despite threats from the Gestapo, she didn't want to leave, lest any family she left behind be hurt, to punish her. Alas, her husband died in 1940, her elder son Hans died in 1942, fighting in the second world war. In 1943 she was forced to evacuate Berlin, and a few months later her house was bombed and a tragically high proportion of her early drawings and print work was consumed by fire.

The Downtrodden - Corpse and nude woman at the post

She died in April 1945 just a couple of weeks before the end of the war. Her extraordinary and historically important works about women, workers, motherhood and grief in particular, continue to move and inspire us.

Rather fortunately for those in Toronto, the AGO has now assembled the second largest collection of her work in the world, so you can be sure that these and many more of her prints and drawings will be available for you to view, post pandemic.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

I am grateful to the AGO for exhibiting this selection, and apologize for photographic imperfections (hand-held).

I am also (once again) grateful to wikipedia and the commons which powers it. So great to be able to link outward and dig widely, without having to constantly run to the shelf for another volume of the encyclopedia (much as I miss 'em).

Finally, here is a striking example of her powerful sculpture - and also an unequalled mode of presentation for a memorial.